For years, we’ve been told that regular exercise is the key to avoiding chronic diseases, and a lot of people have bought into the idea that a good run or gym session can make up for a day of sitting.

But new research, led by a big study from Vanderbilt University, challenges this idea. It turns out, even if you’re super active, sitting for long stretches can still harm your brain, and a workout alone won’t undo that damage.

Sitting for long periods is a major risk factor for brain issues, separate from how much exercise you get. You could easily hit the recommended 150 minutes of exercise each week, but still spend most of your day sitting, which is bad news for your brain.

In fact, the Vanderbilt study found that the link between sitting and brain health issues didn’t go away, no matter how much people exercised. As lead researcher, Marissa Gogniat, PhD, put it, “Reducing your risk for Alzheimer’s disease is not just about working out once a day. Minimizing the time spent sitting, even if you exercise daily, reduces the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease.”

This new research is a wake-up call. Health isn’t just about how much you work out anymore. The real question is: How much time are you spending sitting?

Contents

- 1 Quantifying the Inactive Day: A Modern Epidemic

- 2 The Vanderbilt Study: A Methodological Deep Dive

- 3 Deconstructing the Damage: The Biological Mechanisms of Sedentary Neurotoxicity

- 4 The Genetic Amplifier: The $APOE-\epsilon4$ Connection

- 5 The Solution is in Motion: A Practical Guide to Brain Preservation

- 6 The Power of Movement and a Healthy Lifestyle

Quantifying the Inactive Day: A Modern Epidemic

The scale of inactivity today is shocking. Around 1.8 billion adults, almost one-third of the world, aren’t getting enough physical activity, and that number is expected to rise to 35% by 2030.

This is a major problem, costing the global healthcare system about $27 billion each year and making inactivity the fourth leading cause of death worldwide.

But it’s not just about skipping workouts; it’s about how much time we spend sitting. In the U.S., the average adult spends between six and eight hours sitting each day. Some surveys show it can be as high as 8 hours or more.

The Vanderbilt study took it even further, with participants averaging 13 hours of sitting per day. This shows just how far modern life has pulled us away from the movement our bodies need, creating a serious threat to our brain health down the road.

The Vanderbilt Study: A Methodological Deep Dive

The Vanderbilt study is a game-changer when it comes to understanding the dangers of sitting. Published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia by Gogniat and her team, it stands out because of how carefully it was designed.

They followed 404 older adults for seven years, and unlike many past studies that relied on people reporting their own activity levels (which can be inaccurate), this one used wearable devices to track every movement and moment of stillness.

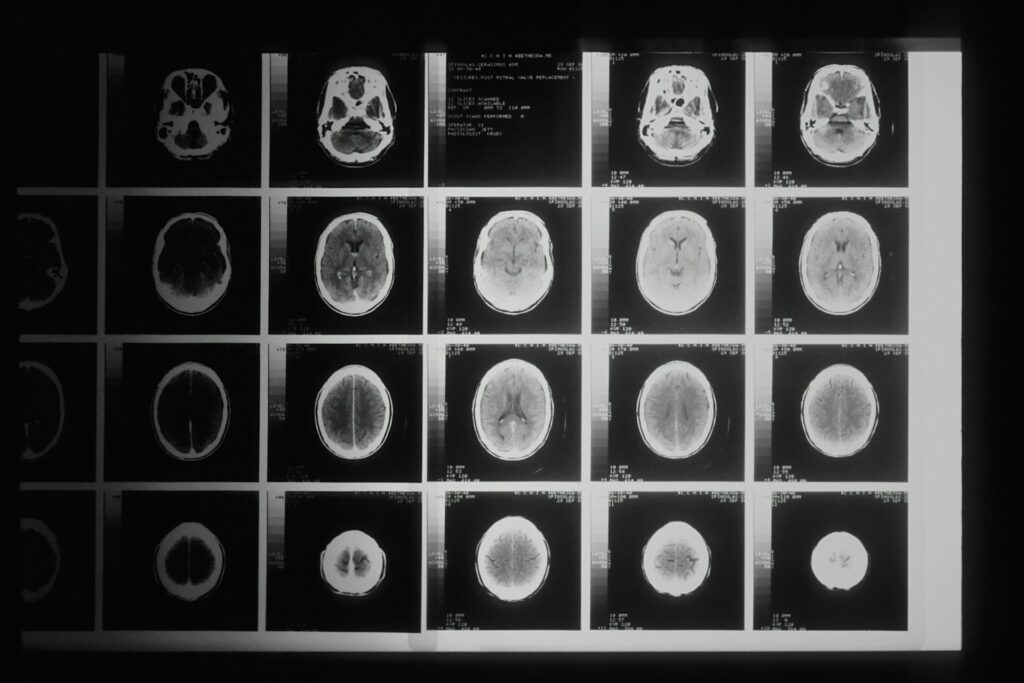

The participants wore research-grade watches for a week, giving the researchers precise data on their activity. That data was then matched with brain scans (using high-resolution 3T MRIs) and cognitive tests over the entire seven years. This thorough approach allowed the researchers to make strong conclusions about how sitting too much can directly affect the brain as we age.

Vanderbilt Study (Gogniat et al., 2025) Snapshot

Participants

404 adults (aged 50 and older) from the Vanderbilt Memory and Aging Project.

Duration

7-year prospective cohort study.

Methodology

Objective activity measurement (actigraphy), 3T brain MRI scans, and longitudinal neuropsychological assessments.

Key Cross-Sectional Findings

At a single point in time, greater sedentary time was associated with a smaller Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging signature and worse episodic memory.

Key Longitudinal Findings

Over seven years, greater sedentary time was linked to faster reductions in hippocampal volume and steeper declines in cognitive functions like naming and processing speed.

Genetic Interaction

The negative effects of sedentary behavior on brain structure and cognition were significantly more pronounced in individuals carrying the $APOE-\epsilon4$ gene, a primary genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease.

Primary Conclusion

Sedentary behavior is an independent risk factor for neurodegeneration and cognitive decline, and its harmful effects are not fully offset by regular exercise.

Deconstructing the Damage: The Biological Mechanisms of Sedentary Neurotoxicity

One of the most concerning findings from the research is that sitting too much can actually lead to shrinkage in parts of the brain that are key for memory. The Vanderbilt study showed that more time spent sitting was linked to faster shrinkage of the hippocampus, the brain’s main hub for learning and memory.

This isn’t the only study to find this; a UCLA study found that sitting too much also led to thinning of the medial temporal lobe, which includes the hippocampus.

To put it simply, think of your brain like a library. When it loses volume, it’s like the shelves in the library starting to decay. The books, your memories and knowledge, are still there, but the system that organizes and retrieves them starts breaking down.

This isn’t just a normal part of aging; thinning in the medial temporal lobe is a known early sign of cognitive decline and diseases like Alzheimer’s. So, all that sitting might be setting off the same damaging processes seen in neurodegenerative conditions.

Mechanism 1: Cerebral Hypoperfusion (The Nutrient Drought)

One of the quickest and most direct ways sitting hurts the brain is by cutting off its supply of nutrients. When we sit for long periods, blood flow to the brain decreases because the big muscles in our legs and core aren’t active. This sluggish circulation means the brain gets less oxygen and fewer essential nutrients, like glucose, that power brain cells and keep them healthy.

Research shows that just three to four hours of sitting can lead to a noticeable drop in blood flow to the brain, creating a kind of “nutrient drought.” When this happens, the brain struggles to function properly, and over time, it can contribute to the shrinkage of key areas, like the hippocampus.

The good news? Studies also show that this decrease in blood flow can be completely avoided by taking short walking breaks; just two minutes of movement every half hour can make a big difference.

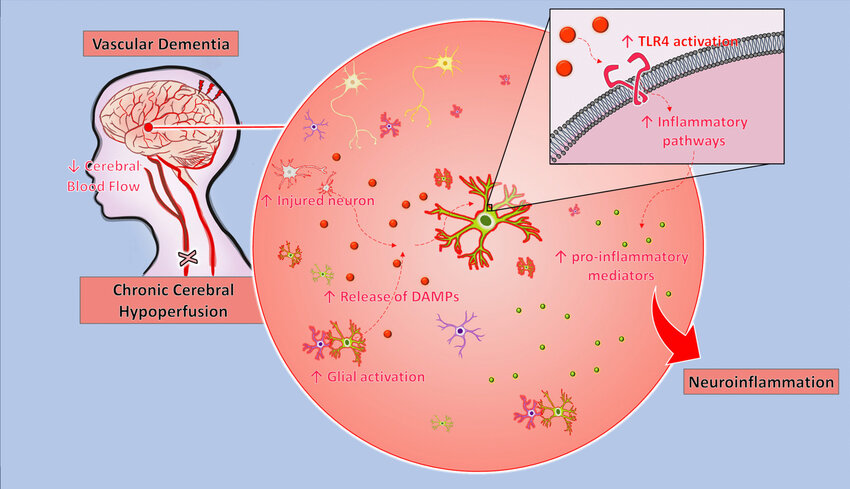

Mechanism 2: The Fire Within (Chronic Neuroinflammation)

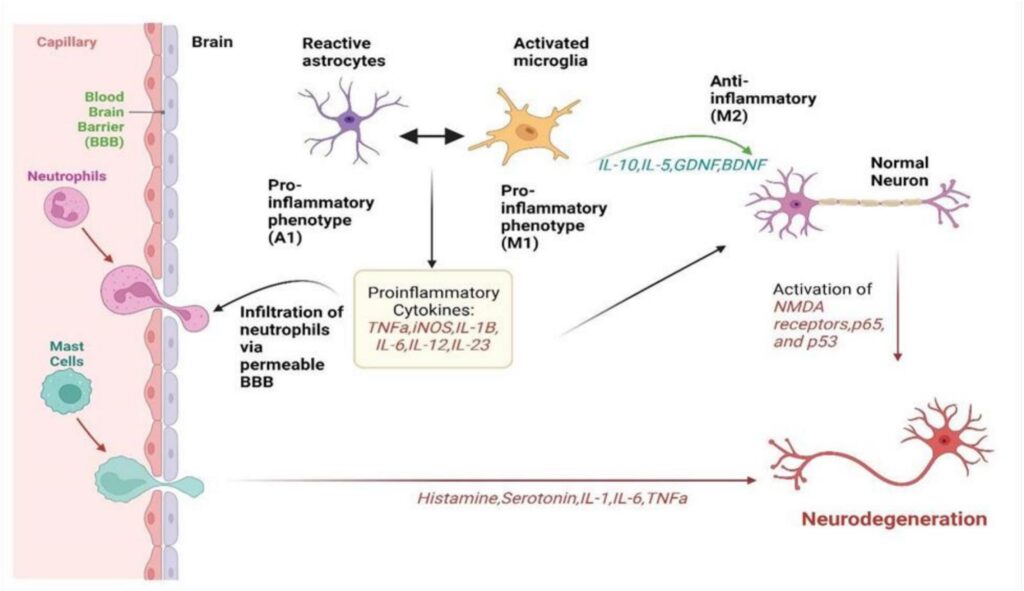

Sitting for too long doesn’t just deprive your brain of nutrients; it also creates a toxic environment inside your body. Research shows that being inactive for long periods leads to chronic, low-level inflammation, where your immune system stays on high alert and constantly releases inflammatory chemicals into your bloodstream. The more hours you spend sitting, the higher these inflammation markers tend to be.

This inflammation doesn’t stay in the body. It can cross into the brain, causing what’s known as neuroinflammation. Neuroinflammation is a key factor in the development of many neurodegenerative diseases. Think of it like a slow-burning fire that gradually damages brain cells and messes with communication between them.

This is why sitting for long periods is so damaging: it creates an inflammatory state that is harmful to brain health and function.

Read: Your Brain is Hiding the Reality from You, And That’s Exactly What Keeps You Alive

Mechanism 3: The Decline of a Miracle Molecule (BDNF)

A third way sitting harms the brain involves a crucial protein called Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), often referred to as “Miracle-Gro for the brain.”

BDNF is essential for keeping brain cells alive, helping new neurons grow, and supporting synaptic plasticity, which is how we learn and form memories. Higher levels of BDNF are linked to a healthy and adaptable brain.

While exercise is known to boost BDNF levels, research shows that being inactive may actually lower them. One study found that people with higher BDNF levels experienced much less brain shrinkage over five years, even when sitting for long periods.

This suggests that BDNF acts as a protective shield for the brain. When we sit too much, we deplete this protective protein, leaving the brain more vulnerable to damage from poor blood flow and inflammation.

These three factors, reduced blood flow, increased inflammation, and lower BDNF, don’t just work independently. They likely form a destructive cycle. Sitting leads to poor circulation, which starves the brain of nutrients, causing stress and impairing its ability to clear waste. This stress sparks inflammation, which then suppresses BDNF production.

With less BDNF, neurons become weaker and more prone to damage, making the brain even more susceptible to further harm. This cycle speeds up brain degeneration, showing just how damaging a sedentary lifestyle can be.

The Genetic Amplifier: The $APOE-\epsilon4$ Connection

Genetics plays a big role in determining whether someone is at risk for Alzheimer’s disease, and one gene in particular, Apolipoprotein E (or $APOE$), has the biggest influence.

$APOE$ comes in three common versions, or alleles: $APOE-\epsilon2$, which seems protective; $APOE-\epsilon3$, the most common and considered neutral; and $APOE-\epsilon4$, which is linked to a much higher risk of Alzheimer’s.

The $APOE-\epsilon4$ allele is the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s, affecting up to 15% of the population. If you inherit one copy of $APOE-\epsilon4$, your risk of dementia is higher. Inheriting two copies, one from each parent, raises that risk even more.

The reason $APOE-\epsilon4$ is so closely tied to Alzheimer’s is that the ApoE4 protein it produces isn’t as good at doing key tasks in the brain, like clearing amyloid-beta plaques (a key feature of Alzheimer’s), transporting fats, and controlling inflammation. These failures help explain why it’s such a big player in the disease.

The Vanderbilt Finding: A Magnified Risk

The Vanderbilt study uncovered a game-changing discovery: the harmful effects of sitting on the brain are much worse for people who carry the $APOE-\epsilon4$ gene. The researchers found that for those with this gene, the link between sedentary behavior, brain shrinkage, and cognitive decline was “stronger” and “more pronounced.” In other words, your genetic makeup can magnify the risks posed by sitting for too long.

This finding shows how lifestyle factors can make genetic vulnerabilities even worse. People with the $APOE-\epsilon4$ gene already have a weakened brain defense system, and a sedentary lifestyle acts like a trigger that speeds up neurodegeneration.

For them, sitting is actively speeding up the damage their genes predispose them to.

Also Read: Harvard Experts Found the Secret to Staying Fit & Healthy After 60 (And It’s Shockingly Simple)

Why Are $\epsilon4$ Carriers More Vulnerable?

People with the $APOE-\epsilon4$ gene are more vulnerable to the effects of sitting because of a dangerous overlap in risk factors. The ApoE4 protein is linked to problems with fat metabolism and a tendency for neuroinflammation.

A sedentary lifestyle also promotes these same issues: systemic inflammation and metabolic imbalance. When you combine the two, the impact is much worse than just adding the risks together. It’s like adding fuel to a fire that’s already burning.

This connection turns a general health tip into a much more urgent, personal recommendation. For someone who knows they carry the $APOE-\epsilon4$ gene, the advice to “sit less” takes on a whole new meaning. The research shows that ignoring this advice could lead to faster brain shrinkage and quicker cognitive decline. This shifts the conversation from broad wellness advice to a critical, personalized strategy for prevention.

The Solution is in Motion: A Practical Guide to Brain Preservation

The key to protecting your brain from the dangers of sitting isn’t about pushing yourself through intense workouts. It’s about changing the way you move throughout the day. Research shows that how you spread activity across your day matters more than a single, tough workout session. The goal is to break up long stretches of sitting.

The good news? Small, simple movements can make a huge difference. Just standing or walking for two minutes every half-hour, or five minutes every hour, can help boost blood flow to your brain and counteract the negative effects of sitting. It’s not only easier to stick with, but it’s also likely to be much more effective at keeping your brain healthy over time.

Evidence-Based Strategies for an Active Life

The best way to reduce sitting is to change your environment to make movement the easy, automatic choice. By setting up little reminders and adjusting your surroundings, you can turn healthy habits into second nature.

At the Office or Desk:

- Use an alarm on your phone or computer to remind you to stand or walk every 30 minutes.

- Switch to an adjustable desk that lets you alternate between sitting and standing.

- Stand up and walk around during phone calls or virtual meetings.

- Instead of emailing a colleague, walk over to their desk to chat.

- When possible, take meetings on the go. Walk around the building or head outside.

At Home:

- Stand up, stretch, or walk around during commercial breaks on TV.

- Instead of sitting to read, try listening to audiobooks or podcasts while walking, gardening, or doing chores.

- Put things you use often, like the TV remote or phone, across the room, so you have to get up to grab them.

During Commutes and Errands:

- Choose a spot at the back of the parking lot to get in a short walk.

- Get off public transportation one stop early and walk the rest of the way.

- Make it a rule to take the stairs, not the elevator or escalator, whenever you can.

By making these small changes, you’ll be moving more without even thinking about it. It’s an easy way to stay active, even on the busiest days.

The Power of Movement and a Healthy Lifestyle

Cutting down on sitting is a powerful tool for protecting your brain, but it’s most effective when combined with a well-rounded, brain-healthy lifestyle. It’s not a magic fix, but it’s an important piece of the puzzle for long-term cognitive health.

Other factors that can lower dementia risk include managing cardiovascular health (especially keeping blood pressure and diabetes in check), addressing hearing loss, getting enough good-quality sleep, staying mentally active with challenging tasks, and avoiding smoking or drinking too much alcohol.

By pairing the habit of sitting less with these other healthy practices, you can create a solid defense against age-related cognitive decline.